The term Jìbĕn Jiànfă (基本劍法) denotes what is generally referred to as the sword basic techniques or basic cuts. It may be translated literally as: the basic, elementary, fundamental (Jìbĕn) methods (Fă), of the straight sword (Jiàn).

The different styles of Tàijíjiàn report a variable number of Jìbĕn Jiànfă, usually ranging from four to thirteen or more. The names of several of them are mentioned already in the Jiàn Jīng, a sword treatise written by Yú Dàyóu around 1560, or in the Wŭbèi Zhì, a military encyclopaedia presumably published in 1620. It is not clear though whether these terms were already referring to the very same techniques as they do today in Tàijíjiàn, and even more so as the Jìbĕn Jiànfă names are not always consistent across styles.

The Yángjiā Mìchuán Tàijíjiàn tradition lists eight Jìbĕn Jiànfă, each corresponding to one of the eight sections in the Kūnlún sword form: Pī, Cì, Liāo, Zhā, Mò, Duò, Tiăo, Huà. A ninth one, Diăn, is also referred to, but is sometimes described as a combination of Pī and Cì, possibly in order to preserve the fit total number of eight pure techniques. Whatever the reason for it, I have the feeling that this description of Diăn as a combination actually acknowledges that the Jìbĕn Jiànfă can be mixed together. I therefore like to consider them not as techniques per se but rather as technical principles that, blended together, make up the actual sword techniques. The so-called basic techniques would thus be simply the techniques which are representative of the Jìbĕn Jiànfă constituting their main, yet not exclusive, component.

A close look at the Chinese characters for the eight Jiànfă of the Yángjiā Mìchuán reveals that four of them (Pī劈, Cì 刺, Duò 剁and Huà 劃) contain the graphic key for the knife, whereas the others (Liāo 撩, Zhā 扎, Mò 抹, Tiăo 挑) contain the key for the hand. We may thus argue that the first four focus on how the blade is actually used for cutting or thrusting while the others rather describe the general movement (raising, whipping, etc.) independently of the weapon. As a matter of fact, the Liāo and Zhā characters can be found in the names of spear, staff or even boxing techniques mentioned in various historical martial arts manuals. The ninth technique, Diăn 點, whose name means pointing, is once again an outsider as it contains none of these keys and would thus exclusively refer to the point of the blade.

The descriptions of the Yángjiā Mìchuán Tàijíjiàn Jìbĕn Jiànfă will not be presented hereafter in their traditional order, which follows the sequence of the corresponding sections in the Kūnlún sword form. Instead, I will present first the four blade techniques before proceeding to the other ones. They are personal interpretations allowing for the above points of view and based upon Master Wang’s teachings and historical texts. Although the contents of this chapter essentially apply to the Yángjiā Mìchuán tradition, it is expected that they may none the less apply more generally, at least in part, to other styles as well.

In Chinese, Pī 劈 means to split, to cut but also to hit, to go straight to. In essence, Pī is a splitting cut that goes straight through the target.

As a basic technique, Pī is simply described as a downward vertical splitting cut. It is often associated with an outside or inside whirl of the sword, which I will not describe here in detail as it is actually not part of the Pī technique and will be more appropriately explained elsewhere.

Although the formal Pī technique is a downward cut, I personally think that the Pī splitting energy can be oriented in any direction. Thus, even horizontal or upward cuts which characteristically split the target open without any slicing movement may somehow be considered akin to this energy.

The formal emblematic Pī technique is prepared by raising the sword handle up to ear level while sinking into the leg opposite to the armed hand. The grip should be relaxed yet firmly secured between the middle fingers and the thumb. The other fingers maintain a relaxed contact with the handle allowing some flexibility in the grip while at the same time keeping control of the blade. In a less formal, less static context, this preparation would be combined with footwork while parrying or evading an attack, seamlessly transforming the defensive action into the riposte.

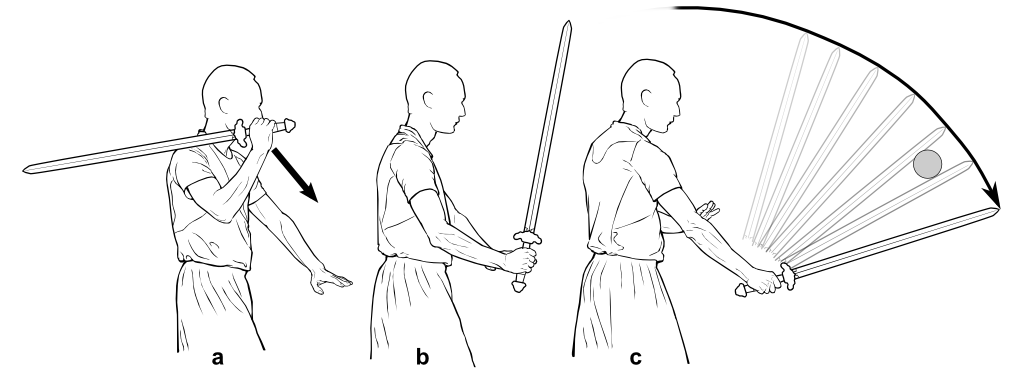

During the first phase of the cut, the hand is thrown downwards along a diagonal, drawing the sword forward and downward in the direction of the pommel to accelerate the blade. The slanted force the hand exerts on the handle thus makes the sword to gradually rotate around its centre of gravity (fig. 1a).

This movement draws its energy from the expansion of the body, which may be seconded by a forward step for increased reach and cutting power.

Then, once the hand has been overtaken by the sword’s centre of gravity (fig. 1b), it stops exerting an action and simply follows the handle, while keeping a relaxed yet firm control of the sword’s trajectory. Thus, the blade is moving freely when it reaches the target with an unperturbed trajectory, and all the kinetic energy accumulated during the acceleration phase is fully transferred into the cut (fig. 1c).

Fig. 1 - Pī cut: (a) Starting from a high position of the sword, the right hand draws the sword handle downwards to accelerate the blade; (b) shows the end of the acceleration phase, from now on, the hand will not exert any more action on the handle; (c) the hand follows the handle with only a firm control of the sword’s trajectory so that the blade is allowed to move freely though the target represented here by a grey circle. Note that the trajectory of the blade tip is not circular but an elongated arc.

It is absolutely crucial that the flat is perfectly aligned with the blade trajectory to make sure that the weight of the blade lies behind the edge to push it through the target. If the blade hits the target at an angle, no matter how small, it tends to rotate on its axis and may bounce back dangerously instead of nicely cutting through the target. On the other hand, when the alignment is correct and the grip is relaxed, the blade will flash through the target without any appreciable feedback.

After the cut, the handle naturally presses against the heel of the hand and the fingers tighten their grip to bring the sword to a halt at waist level in a protective position without any tension nor bounce. Thanks to a proper body alignment, the sword’s energy is thus returned to the body, helping to recentre oneself and make ready for the next technique.

The verb Huà 劃 means to delimit, to draw. The same character is also used as a variant of the word for an individual stroke in a Chinese character. Along with the fact that the left part of this character is indeed the key for the brush, these observations tend to suggest that the technique somehow evokes the notion of calligraphy, of writing or drawing.

The emblematic technique is presented in the Yángjiā Mìchuán as a horizontal cut or a large horizontal movement for keeping opponents away. The idea is here to sweep space with the sword to delimit the largest possible area around oneself and slash anyone closing in.

In a more general perspective, Huà cuts do not need to always be horizontal and encompass a whole range of distances, from very long slashing cuts with the very tip of the blade, to very close-range drawing cuts with the whole edge. In any case, all Huà cuts have in common to be long-energy slicing movements where the blade actually draws a groove in the target instead of splitting it open at once like the short-energy Pī cut does.

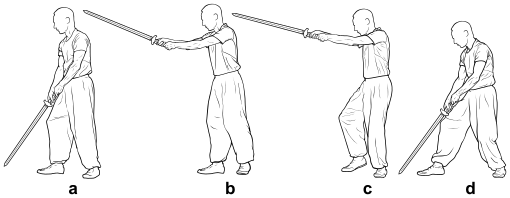

When performing a long-range Huà, the sword is thrown forward and, when the arm has nearly reached its full extension, slightly before the blade hits the target, the grip is gently tightened to secure the connection between the centres of the sword and the body. The rotation thus continues around the shoulder while the sword is pulling the body forward until maximal reach is achieved (fig. 2a-c). Then, the grip acting as a fulcrum, the sword’s inertia pushes back the handle against the heel of the hand. This results in a slicing cut and a backward movement that centres the body back into a guard stance (fig. 2d-f).

Fig. 2 - Long-range Huà cut: (a) Starting from a high position of the sword, (b) the right hand throws the pommel forwards; (c) shows the end of the active phase of the technique; (d) to (f) during the passive phase, the sword’s inertia pushes the hand backwards, performing the slicing cut and centring the body back into position.

At closer range the dynamics of the Huà cut rely less on sword’s inertia but more on body structure and movement. Once the edge of the blade is in contact with the target, the slicing cut is generated by pressing the edge against the target while pulling it in a direction parallel to the blade, either with a step or a rotation of the body. On some occasions, in particular when one is passing behind the opponent’s back, it may be possible to perform a short range Huà with the false edge.

Beside being a slicing cut, Huà can also be used to keep the opponents at distance or to incite them to react so we may exploit their action and take control of the rhythm. This is achieved either performing an uncommitted long-range Huà or whirling the sword while advancing. This should definitely be done at a distance close enough to be perceived clearly as a threat even though we may be out of measure when doing so. The ideal distance is actually the very upper limit of the short measure, at which distance, a hit being uncertain yet perfectly plausible, the opponent will feel compelled to react defensively. It is crucial here to get ready to follow up with a more committed attack or with a blade control depending on the opponent’s reaction. This second intention will thus ensure to keep the initiative and exploit the opponent’s action.

While withdrawing after an unsuccessful attack, we may want to keep our opponent away with a series whirling cuts performed in a row, which Master Wang Yennien described as being Huà cuts as well. This application of the technique perfectly fits the translation to delimit as it creates indeed a zone of security and prevents the opponent from catching up and attacking us while we are getting out of measure.

The word Cì 刺, which means to thrust, to pierce, to stab, is used in the Wŭbèi Zhì as a generic term referring to all thrusting techniques. It is mentioned as well in other ancient treatises to describe thrusts with a variety of weapons.

In the Yángjiā Mìchuán tradition, Cì can be defined as a powerful upward or horizontal thrust where the point is pushed forcefully through the target.

Fig. 3 - At the end of the long Cì thrust, the sword is aligned with the left hip but its point is centred, aiming at the base of the throat. The power of the whole body structure is concentrated into the sword to forcefully push the tip through the target.

The formal technique is habitually performed starting on the right foot, left leg forward, either with a passing step (long Cì) or with a simple transfer of the weight onto the left foot (short Cì). In the formal context of drills and routine practice, the short Cì is aimed at the belly and the long one at the throat. When sparring though, other parts of the body, such as the torso or even the face, are also targeted.

Long or short, the technique invariably starts by creating in the body a spiral structure connecting the left foot to the sword. As soon as the waist starts moving, the right arm pushes on the handle and rises in a spiralling movement that ends up with a flat horizontal sword position, the pommel oriented towards the left hip. Simultaneously, the weight is transferred onto the left foot. The grip gradually adapts to achieve a uninterrupted connection between the hand and the handle, without any kink, suitable for pushing the sword forward effortlessly. The adjustment of the grip also permits the exertion on the handle of an oblique action reaching through the guard for a point just beyond to generate a pivot point at the tip and stabilize it1.

In the long version of the technique, a greater reach is achieved thanks to a passing step of the right foot. The right arm must be extended before stepping forward in order to improve the precision of the thrust and to keep the body as far as possible from danger behind the sword. Further protection can also be achieved by binding the opponent’s blade to control it with the guard or the forte.

Ideally, the right heel should touch the ground exactly at the same time as the blade tip reaches the target. The relaxation of the structure then completes the passing step while pushing the blade through. In doing so, it is important not to fall into the right leg to keep our ability to withdraw quickly if needed. This does not mean though that the weight should not be in any way transferred onto the right leg, but that the polarity empty/full between the two legs should be maintained under all circumstances so as to avoid double weight. A powerful yet mobile structure is thus achieved by the generation of an arc of force, going from the left foot, traversing the back, spiralling along the right arm to reach the tip of the blade, and backed up by the spiral in the left arm and sword fingers.

Besides the above emblematic form, the Cì techniques may encompass other powerful thrusts leveraging the body structure to push the sword forward in a, clockwise or anticlockwise, spiral. In all those techniques, a protective cone is created, whose point aims at the target and within which one can step in, safely hidden behind one’s own sword.

The translation of Duò 剁, referring to the cooking term to mince, somehow suggests repetition and cutting using a part of the blade further away from the tip than Pı̄. The movement itself is a combination of a forward extension with some sort of shearing, as if using a large cooking knife to mince herbs or vegetables.

In the Yángjiā Mìchuán tradition, the emblematic Duò is performed with both arms extended almost in line with the sword’s blade (fig. 4).

Duò in the forward direction. From a low guard (a), raise the sword with a transfer of the weight onto the right foot (b), invert polarity and transfer the weight back onto the left foot (c), drop the sword while sinking in the left leg and advancing the right foot.

Even though both hands are in contact with the handle, this should not be mistaken for a true double handed grip of the sword. While raising the sword and advancing, the right hand holds the sword while the left hand provides the structure and power by acting on the pommel along the direction of the blade. Power originates in the weight transfer from the rear leg onto the fore leg, is transmitted to the sword by the left/rear hand with the right/fore hand exactly and passively balancing the forces to effortlessly generate the technique. This combination of the right hand’s passive role with the left hand’s action creates a polarity resulting in a movement of the sword perpendicular to the axis of the right arm. An effective connexion between the waist and the sword will thus allow the explosive expression of the Duò technique. This method somehow echoes the precepts found in the Jiàn Jı̄ng stating that, when wielding a double-handed sword, power is first in the waist, then in the rear hand, and finally in the fore hand. When lowering the sword, the roles of both hands are inverted. For the retreating Duò, although the combination of forces is the same, the right hand is active when raising the sword, and passive otherwise (fig. 5). As a rule of thumb, advancing or retreating, the active hand is always the one on the same side as the foot that is moving.

(a) To perform a forward rising Duò, the left hand pushes the handle in the direction of the blade tip while the right arm passively balances the pushing force. Due to the angle between the pushing direction and the right arm, the resulting force perpendicular to the right arm pushes the sword upwards. If stepping backwards, the same forces apply but the right hand is actively pulling the sword whereas the left hand passively balances this action.

(b) To perform a forward descending Duò, the right hand pushes the handle while the left arm passively balances this force. The resulting force perpendicular to the left arm, draws the sword downwards. In the backward version of the technique, the left hand pulls the sword while the right hand is passive.

Since, when cooking, herbs are usually minced by cutting downwards, we may argue that the active phase of Duò is the descending one. However, if we examine attentively the actual movement of a kitchen knife when mincing, we may discover that its form when cutting actually corresponds to the rising phase of Duò. The main difference is that the tip of the knife stays down in contact with the table whereas the point of the sword rises up. But, in both cases, the edge follows the same movement relative to the tip. However, it is perfectly possible to be active in both phases, the actual passive phase being the transition movement between the ascending and descending parts of the technique. Thus, Duò can be a raising thrust or cut as well as a descending cut, or, combined with Mò energy, an action on the opponent’s blade, either ascending to intercept and deflect or descending to shear.

It is worth noting at this point that, since both hands are in contact with the hilt, the sword is always in line with the axis of the body. This axis is more to the left when we are on our left foot, in the low on-guard position that precedes the ascending forward phase of Duò. Then, during the lifting phase of the movement, the axis is shifting to the right before being transferred back to the left when descending. Therefore, in the deflect/shear application of Duò in combination with Mò, during the upward interception/deflection, transferring the weight onto the right/forward leg gently pushes the opponent’s tip away, allowing the descending shear to naturally aim at the centre of the opponent’s sword, deflecting it further to open the way for a hit while preventing any counter attack.

Although the classic movement is done with two hands, it is also possible to perform a Duò with one hand only. In this case, the heel of the hand plays the same role as the rear hand in the two-handed version while the first three fingers the index and middle fingers, and the thumb play the part of the forehand.

During the ascending phase, the handle of the sword is pushed forwards by the heel of the hand and simultaneously pulled by the first three fingers. Given a good structure in the on-guard position, it is then possible, even with only one hand, to swiftly and effortlessly raise the sword from a low to a high position, for thrusting or engaging. The alignment of the sword is quite similar to the two-handed version, with the tip of the blade in line with the body axis. However, the structure is not as strong as in the two-handed Duò and, as a result, the shearing actions are not as powerful. However, this version of the movement is useful for quickly engaging the opponent’s blade or a sudden attack from a lower guard.

Translating as to raise, to lift, to sprinkle, Liāo 撩 is found in various ancient manuals for different weapons. The Yángjiā Mìchuán tradition describes the technique as an upward cut, but it is sometimes also considered as a defensive action used to parry or deflect an incoming attack. Technical details will vary according to the type of cut performed, splitting or drawing upward cut, or whether Liāo is used to parry. All variations though have in common the upward direction of the movement, as if raising a curtain.

Zhā 扎 is a downward thrust.

Mò 抹 encompasses all the techniques that control the centre of the opponent’s blade.

Tiăo 挑 means to rise, to provoke something or someone, to poke the fire. It is a swift cut performed with the false edge.

Diăn 點 is a swift thrust or light cut performed with the very tip of the blade.

See chapter The Chinese sword for more details on pivot points.↩

Frédéric Plewniak 2014.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.